Essays Current Research ReviewsContributorsAnnouncements

Home

Fellow Travellers: James Lumsdenís and James Houstonís Summer Tour to the Highlands and Northern Isles, 1878 by Jill Farleigh Tattam Wolfe

On Saturday, June 22 1878, readers of The Shetland Times would have observed this bold advertisement in the General Notices column:

Tam O’Shanter |

One hundred and fifty years later, this advertisement still conveys a certain frisson, providing the “hook” of Robert Burns to capture the reader’s attention and then their patronage at an evening of “musical entertainment”. Its confident merging of audiences offers an especially intimate insight into the cultural life of Shetland that summer.

Old friends were indeed back in town, an announcement that referred not only to Lumsden’s company but also to the repertoire that promised an evening with familiar Scottish characters. This marked his sixth visit in what was becoming an annual progression around the Highlands and Northern Isles. He could afford to assume a self-confident tone. Audiences had become accustomed to regular visits from “that most pleasant and most popular of all humorous singers who ever came to Lerwick” (Manson 181).

Lumsden was in charge of a family-run business that played different venues around Scotland and the north of England, including soirees in temperance halls, churches and Sabbath schools, Masonic Halls and working men’s clubs. Earlier that March, Lumsden and His Scottish Minstrels “forty in number now and giving their miscellaneous and attractive entertainment with great success” performed in Edinburgh at Weldon’s Circus (17 March 1878 The Era). Billing his troupe as minstrels indicates that Lumsden drew his strength from the traditions of Scottish variety and music halls, travelling from place to place and not anchored at any particular venue, though by 1870 he was a familiar sight on the Glasgow stage. In addition to a North American tour in 1875-77, Lumsden and his “family” made frequent appearances in Aberdeen. He also returned regularly to the Northern Isles appearing in Lerwick between 1873 and 1884 when in July of that year he performed in the newly opened Town Hall (26 July 1884The Shetland Times). By 1898, Lumsden would again appear in North America; New York being among several stops on a North American tour that targeted the Scottish diaspora (Maloney 93).

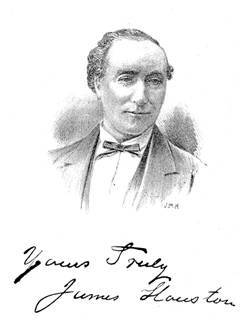

The tour in 1878 by Lumsden’s newly renamed “National Ballad and Comic Entertainment” therefore marks a mid way point in his career. His performances were now regularly reviewed in the professional journal The Era. Indicative of Lumsden’s status as a popular entertainer is the presence in his company of James Houston, whom Lumsden had engaged for the summer. Houston was in all respects a national star who had built a career for himself in the music halls of Glasgow and other venues throughout Scotland. Now 50 years old, he had an established reputation as an actor and was “regarded by his audiences as an outstanding Scotch comic” (Findlay 16). In fact, Houston had just ended his engagement at the Theatre Royal Glasgow where he had played the Bailey in Rob Roy, a specialty of the House. The Era correspondent in an odd premonition of events that later occurred in Lerwick remarked: “Mr Houston’s Bailie is the best we have seen of late years. We cannot, however, recommend his taste in introducing allusions to modern topics” (9 June 1878 The Era).

Glasgow at this time was the “centre of a vibrant Scottish performing culture, producing its own stars (Scottish)…with a specific Scottish ambience (Maloney 215). Houston’s Autobiography makes clear that he was well known for his interpretations of the humorous parts in the revivals of the Waverley dramas, especially his portrayal of the Glaswegian magistrate Bailie Nicol Jarvie in Rob Roy which he performed in May 1875 at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow “feeling as cool as a cucumber” to a “splendid reception” (67). His comic rendition of Dumbiedykes from the Heart of Midlothian and Dandie Dinmont in Guy Mannering were equally well received: “Houston has the ball at his foot as regards the humorous parts in the “Waverley drama’s”: there is no competitor on the boards” (69). Houston maintained two careers “dividing his attention between the Theatre and the concert platform” (78). Lumsden, on the other hand, had a career on the concert stage in variety and music halls as a Scottish entertainer, rather than in the theatre. But in the summer of 1878, these two legends in their own time were together “concertising awa’ in the north” (86-87).

James Houston from his Autobiography.

Under the heading Musical Entertainments, The Shetland Times in its July 13, 1878 review notes: “Mr Lumsden is so well known here that it is scarcely necessary to say that the concerts were well attended.” James Houston’s Autobiography published in 1889 contributes to the reconstruction of these popular concerts by providing a remarkable account of his one and only appearance in Lerwick in association with Lumsden. It offers self-promoting but none the less perceptive insights into the nature of Scottish entertainment practices in the last quarter of the 19th century.Captured in some detail are the organizational and logistical strategies employed by Lumsden when he led his National Ballad and Comic Entertainment July concert tour to the north. The tour included two nights in Thurso (July 1st and 2nd 1878), one night in Castletown and two nights in Wick (July 4th and 5th) before the entertainers sailed for Lerwick on Saturday, arriving on Sunday, and opened their three-day series of performances on Monday. The company included James Lumsden, and his ten-year-old son Arthur who was the piano accompanist, as well as James Houston, and Isa Robertson. It was what Houston would call “a scratch company, at least several actors, not members of a stock company” (47). This arrangement worked to the advantage of the three adults who were on the “share principle.” According to Houston, this meant that young Lumsden was paid 3 pounds per week and railway expenses and the rest of the take was divided among the three adults after “squaring off all debts due, providing a most successful speculation in every way...and with the splendid houses, and, company so few, the dividend weekly was immense... we gave the audience as happy a night as I have seen given, when there were three times three of a company” (81). Such a financially advantageous arrangement would have off set the punishing schedule of this summer tour, only made possible by newly improved transportation links by train from Inverness on the Far North Line (opened in 1874) to Wick and Thurso and then via steamer to Kirkwall and Lerwick.

What was the nature of the “national” comic entertainment performed by Lumsden’s National Ballad and Comic Company? The Shetland Times onJuly 13 1878 alludes to a dialogue of “Tam O’Shanter” as well as “musical intertainments” [sic]. This suggests that the two men sang their own songs and worked in their own comic sketches, using recycled material that incorporated local allusions appropriate to the venue at the moment. Both, it seems, were natural raconteurs. This tour also marked the third appearance in Lerwick of Isa Robertson who was “a soprano of great ability, whose forte was Scotch songs, which she sang with fine effect” (Manson 181). She and Lumsden often took part in duets and “one of their stock pieces, namely the A.B.C. always brought down the house” (Manson 181). Presumably this was the familiar children’s alphabet song but now reconfigured and turned to advantage satirically: “though never vulgar or coarse […] never overstrained or unnatural” (Manson 181). Unfortunately, on the occasion of the 1878 summer tour, the brief Shetland Times review is dominated by the account of an event that “marred the evening’s entertainment”. We, in the wings, so to speak, can still get a whiff of this event through Houston’s Autobiography. Handily providing details for this concert tour, it is possible partially to reconstruct the nature of the entertainment offered over three nights, and in particular the final evening’s performance and the events that followed, which caused in Houston’s words: “a most unlooked-for predicament”(87).

Beginning at 8 o’clock young Lumsden opened the performance playing: “a selection of Scotch airs on the piano [...] dressed as a little highlander, Sporran, kilts an’ a’ that; and, being a round faced and healthy boy, he looked very nice and was a favourite with the mamma’s and their daughters” (81). Houston’s detailed description of young Lumsden’s attire and his reception by Lerwegian audiences indicates that the hybrid Highland- Lowlander comic figure, so prevalent in popular entertainment by the end of the century, was already assimilated and embedded by 1878. Attire aside, Lumsden “played pieces and accompanied the singers with care and composure much beyond his years (81).” Musical accompaniment was important. In lieu of an orchestra, the lad played a central part in the success of the evening’s performance providing the incidental music during the dialogues of his father and Houston, and accompanying Isa Robertson. After his musical interlude, Isa Robertson “gave the Songs of Scott.” Then Lumsden and Houston, took the stage giving two turns each, which is to say that in the first part of the programme each actor appeared twice.

Houston, gauging from the songs and sketches appended to his Autobiography employed an array of material, much of it original and appropriate to the moment. During his three nights in Lerwick, the audience might have seen him in his celebrated role of Bailie Nicol Jarvie in Rob Roy, “displaying hisgenuine appreciation of the part,” according to Walter Baynham in his 1892 history of the Glasgow stage (100), or Dandy Dinmont in Guy Mannering. In this role Houston would lead off with a dance. After one such caper he injured his ankle, which caused intense pain and led to a comment noted in his Autobiography about the tribulations of actors:

Little do our friends before us know

The dreadful trials actors undergo;

For while they laugh, and seem devoid of cares,

Many a secret sigh and tears is theirs (89).

The first half of the programme included a series of songs with spoken dialogue such as Peter Carmichael, or Scottish Oatmeal. The first stanza of Scottish Oatmeal reprinted in Houston’s Autobiography gives contemporary readers the flavour of this popular ditty:

Let epicures brag o’their Frenchified dishes,

Their truffles and puddocks, ragaut and fed veal-

A’ that I ask for, an’ a’ that I wish is,

Aye plenty o’ soor milk an’ Scottish oatmeal.

The dandies for dainties may constantly forage,

But there’s naethin’ agrees wi’ a Scotchman sae weel

As a great muckle bowl fu’ o guid halesome parritch

O’ Smith, the famed miller’s best Scottish oatmeal (191).

This song would reappear in accounts of Lumsden’s New Years performance at the Aberdeen Temperance Society Grand Festival in the Grand Music Hall Aberdeen in 1879 (4 January 1879 Aberdeen Journal). A piano overture concluded the first part of the programme.

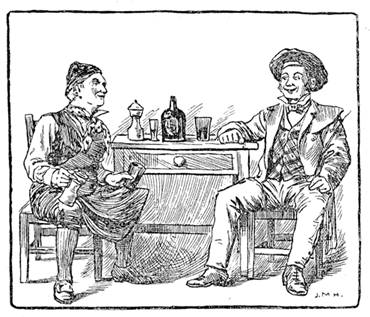

The second part of the performance according to Houston was “the celebrated sketch of “Tam O’Shanter and Souter Johnnie”” (81-82). Lumsden played Tam O’Shanter to Houston’s Souter Johnny, Tams “ancient, trusty, droughty cronie” who “tauld his queerest stories; The landlord´s laugh was ready chorus”(Burns.s.5). The audiences, according to The Shetland Times July 13 1878 review found Lumsden and his company: “broadly humorous in their dialogue of Burn’s poem Tam o’Shanter”.By selecting Burn’s poem Tam o’ Shanter, the two men were drawing on rich linguistic material that “capitalized on the great “enormous popularity” of Robert Burns” and “brought his work, in however diluted a form, to new audiences” (Cameron 430).

Image from Houston’s Autobiography

Houston and Lumsden in “Tam O’ Shanter and Souter Johnnie”.

Illustration by J.M. Hamilton

The half drunken philosophizing of Tam has comic potential for talented actors who could play off each other, mulling over various “pleasures” both secular and profane. Many lines in the poem are sources for comic interpretation such as:

Ah, Tam! Ah, Tam! Thou’ll get thy fairin!

In hell they’ll roast thee like a herrin!

In vain thy Kate awaits thy commin!

Kate soon will be a woefu’ woman! (Burns.18).

According to his Autobiography, Houston was known for his “pawky enunciation of the lines allocated to Kate” and was “a most decided hit in the part”. In Lerwick he would have “caused much laughter by his faithful representation of Tam’s masculine wife” (69) if he had chosen to perform as Kate during one of the performances. In any case, the results of disregarding the advice of a wife might have struck a receptive cord with the men and women in the audience. Similarly, some moral advice in the final coda about the “dangers” of drink would have elicited a chuckle from an audience well versed in temperance messages. Thus issues of morality and taste could be explored and even improvised on the spot, especially when the lines, as in the final stanza, were delivered by two experienced performers:

No wha’ this tale o truth shall read;

Ilk man and mother’s son take heed;

Whene’er to drink you are inclin’d,

Or cutty sarks run in your mind,

Think! ye may buy the joys o’er dear:

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare (Burns s.40).

Burns’ poem, however, is more than simply the story of two men spending an evening drinking and an encounter with witches dancing with the devil. Whether Lumsden and Houston chose to exploit the poem’s subtle exploration of the strident message of Calvinism and its harsh assessment about human nature is pure conjecture. It certainly would not have been difficult to work into their routine interactive exchanges that alluded to the moralistic intrusiveness of more zealous members of the wider religious community within Scotland. What is known is that jokes were cracked and punning songs were sung that included references of local interest in this crowd-pleasing sketch. The evening’s entertainment “finished up about 10:15 p.m., with a Scotch reel that sent the audience away in the best of spirits” (Houston 82).

The Shetland Times review of the final performance offers an alternative perspective about the success of the troupes visit. For the moment the newspaper reflected the traditional Calvinist distrust of popular entertainment while at the same time nimbly asserting it’s own role as moral adjudicator in the incident involving an unfortunate gaffe made by Houston during a performance. Thereviewer’s censorious comments were directed at Houston who had worked, perhaps even adlibbed into a comic song an allusion to a local woman. The song that caused the public reprimand was Peter Carmichael with spoken dialogue and delivered as a turn. Adapting material to suit the occasion and locale was a common practice in concert routines but in this case Houston was perceived as having over stepped the boundaries and “tended to coarseness in some of his presentations which we can assure him does not take well with a Lerwick audience” (13 July 1878 Shetland Times). This is an interesting statement as it suggests that the audience was self-selecting. They knew what was inappropriate. “Coarseness” was a frequent term used by Victorians and conjured up a popular stereotype of the comic actor who always ran the risk of being considered vulgar and offensive. “Mr Houston may have been put up to it by way of a joke, not knowing who the individual was of whom he was speaking,” continues the review “if so, we cannot refrain from saying that it was a very low joke, causing much annoyance to an inoffensive individual.” It is important to note here that Houston’s appeal within the context of a respectable entertainer-cum-comic actor partnership was called into question. This was no trifling affair as it reflected on Lumden’s National Ballad and Comic Entertainment in general, with the potential for financial losses at the box office and in particular: “landing the singer into a considerable pecuniary loss.” It is clear from the tone of the review that The Shetland Times had its own sense of ‘audience’ and was accustomed to speak with self- confidence on its behalf. “We applaud Miss Stove for her action in this matter [and] we may safely add that anything that was said about her on this occasion will not lessen her in the esteem of her friends” concluded the review.

The newspaper’s comments give no further information about the incident. Houston’s Autobiography, however,does. According to programming protocol, the song Peter Carmichael that was part of Houston’s standard repertoire would have been performed in the first part of the evening’s programme. Houston often adapted the dialogue. In Lerwick, he inserted the name of a local woman although he would later deny this. One cannot help wondering if Houston was cognisant of the unique demographics of Shetland and Lerwick in particular which at the time of his performance, was succinctly summed up as “a women’s town” (Abrams 76). Had he in fact been encouraged to “cock a snook” at a certain independent businesswoman? Whatever the case may be, Houston’s account provides us with the lyrics to the song. It was the second verse that caused Houston to “put his foot in it”:

My name’s Peter Carmichael, I cam’ frae Kilsyth

Tae Glasgow on purpose tae look for a wife;

But I canna get ane, let me dae what I can,

Is there onie lass here lookin’ oot for a man?

Wi’ a braw, decent kimmer I fain would elope,

But somehoo, whenever the question I pop,

They glow’r in my face, and say, with a smile,

“Peter Carmichael, I don’t like your style.”

I took Katie Munn down tae Largs at the Fair

Expecting tae win her affections doon there,

But she met wi’ a lad she kent here at hame,

And left me tae drink the saut water my lane.

Noo, what had I din that she could tak’ amiss?

I never yet ventured the length o’ a kiss;

And her last partin’ words I can ne’er reconcile,

She says, “Peter Carmichael, I don’t like your style”

(Houston 177-178).

The offence occurred when Houston changed the name of the woman mentioned in the second stanza to Hester Stove, the twenty-five year old daughter of John Stove who ran a local grocer’s shop on Commercial Street where confectionery was sold (Robertson 199). Unbeknownst to Houston, this incident was reported in the Glasgow Daily Mail. The article was then reprinted in the local Inverness newspaper, the North British Daily Mail and brought to Houston’s attention upon his arrival in Inverness some weeks later. This detail is telling. Popular entertainers were scrutinized carefully in the columns of local newspapers and reviews and gossip were shared amongst the press. Houston turned some of these reviews to his advantage as testimonials and even reprinted many of these effusive “Opinions of the Press” in his Autobiography. But a damning review, especially when it involved issues of impropriety could financially break a visit, and even sully a career. In this instance, Houston’s reputation preceded him. Consequently he included the Daily Mail report of the Lerwick kerfuffle in its entirety in his Autobiography so that he could “throw a little more light on that subject” and protect his reputation.

|

A Glasgow Comedian in trouble in the North

It is well known that the shaft from a bow, drawn at a venture, will sometimes reach the mark, and the latest case in point occurred to disquiet the peace of mind of our townsman, Mr James Houston, the celebrated vocal comedian, and well-known representative of ‘Bailie Nicol Jarvie.’ He has been out with a concert party for about a month ‘working’ the north of Scotland, and they reached as near to the pole as Lerwick, when the incident we refer to occurred. In the course of the evening, at an entertainment given by them there, Mr Houston gave one of his best known effusions (his own writing, by the way), namely-‘Peter Carmichael’ and it was through this that he put his foot in it. (The offending stanza is duplicated here in the newspaper report.) Mr. Houston declared that the name of the fickle fair one, like the names in all his songs, was purely fictitious; but by a coincidence, which seems simply marvellous, there happens to be in the town a maiden lady who keeps a ‘sweetie’ shop, above the door of which can be plainly seen the name of Ester Stove, which the occupant of the premises avers to be her correct designation. The Christian name, it will be observed, is spelled slightly different; but, even taking this into account, the coincidence, as we have said, is singularly striking- to Mr Houston it is something more, it is considerably annoying. Of course some ‘good natured friend’ brought the matter before the maiden’s notice next morning, who immediately brought it before her man of business, who at once despatched a letter to the vocalist demanding 10 pounds and an apology for what he had done. On this letter being disregarded the result was a summons to appear before the Sheriff in an action for wounded feelings, the damages being laid at 50 pounds. The case came on in absence of the defender who, however, has been informed that owing to some informality in the wording of the summons-some flaw in the indictment- it was postponed for a week. We shall hear how the unhappy coincidence case terminates. Mr Houston declares if he is to be brought up for every name that answers to some one in the towns he visits he will be in Othello’s condition with his occupation gone(83-84). |

Contradicting the Daily Mail account, Houston notes that upon receipt of the lawyer’s letter, he and a friend went around promptly to the sweet shop to make amends by offering an apology and the payment of 10 pounds. This peace offering was all in vain as the “rather good looking and also high blooded” Miss Stove was “so eaten up with passion” she did not allow Houston to get a word in edgewise. “Raising herself up to a majestic attitude” and “with a withering look she seemed to say-“O that mine eyes had heaven’s own lightening, thus with a look that I might blast you”, the plaintiff refused Houston’s apology and “rushed up the stairs leaving my friend and I bewildered […] and as she ascended [we] could hear her mutter “a hundred pounds or more ere I am done with you” (84). Histrionic descriptions of her appearance aside, it is apparent that Miss Stove was in a litigious mood and eager to defend her image and status as a respectable member of the community. As Mary Prior has shown in her study Fond Hopes Destroyed: Breach of Promise Cases in Shetland, 1823-1900 (2005) Shetland women were not shy in defending their honour. Hester Stove consequently was not swayed by Houston’s charm and stood her ground.

The morning (Thursday) following the incident the company departed for Kirkwall and performances there on Friday and Saturday night. Instructing a friend who “was a man of business” to look after the case, Houston departed Lerwick but he also had the foresight to leave “a copy of the song for the Sheriff so that he might be better able to understand the case.” The entire affair cost Houston “ a couple of pounds besides the annoyance” after the “Sheriff threw [the case] out at once saying, “it was the most trifling affair that ever came before him” (86). This ends Houston’s account but The Shetland Times in the Local and District News Column for July 20 1878 provides the official version when it reported:

Stove vs Houston. This case was called in court, before Sheriff Rampini, and was then remitted to the Ordinary Roll. We understand that since that time the matter has been arranged, Mr Houston’s agent having agreed on his behalf to make a suitable apology and to pay any expenses incurred in raising the action.

Houston’s own richly detailed version of the incident goes some way to clarify the incident, and in turn provided him with a comic routine to work up, penning topical verses on his way home from the north which he sang at the City Hall Saturday Evening Concert, upon his return to Glasgow. Never one to miss an opportunity to entertain and amuse with fresh material, this ditty about his experience reveals his skill at writing material that was almost up to the moment, both personally and politically. It also affords a humorous retelling, one final salvo so to speak, about the eventful visit to Lerwick and makes Houston the focus of his own joke. This lengthy rhyming verse was sung to the tune “Irish Washer-woman”:

Kind friends I’m richt happy to see you again;

Since the last time we met I have been far frae hame;

When last winter’s concerts had come to an en’,

What to do in the summer I didna weel ken.

I thocht on the east, I thocht on the west,

But I thocht that the north it would suit me the best;

So I packed up my traps-left my friends a’ in smiles,

And set off on tour to the famed Shetland Isles.

Chorus

But I’ll gie ye correct, if ye listen to me,

An account of my journey by land and by sea,

Frae the wild Pentland Firth to the famed Firth of Forth,

When I went concertising awa’ in the north.

Frae sax in the morning till eleven at nicht

In a close railway carriage is no very bricht,

But though I dina like it, it would maybe suit you;

“Taste’s a’, said the man, when he kissed his ane coo.

I got into a steamer at a place they ca’d Wick,

Where the fishermen’s boats there are lying so thick;

Then I heaved for a night and a day up and down,

Till I landed at Lerwick- Shetland’s great County toon.

But I’ll gie ye correct, etc.

Some houses in Lerwick I could notice that they

In the auld smuggling times, had been built in the Bay,

But for a soom in the morning it was handy for me

To jump oot o’ my bed and pop into the sea.

And for fishing I never saw naething sae fine,

Out the window I just had to throw o’ er my line,

And before the auld wife had a kettle near fizzen

I would catch something less than a couple o’ dizzen.

But I’ll gie ye correct, etc.

Our concerts in Lerwick turned out a success,

But, as bad luck was ha ‘e it, I got in a mess;

I sang “Peter Carmichael,” and mentioned the name

Of a certain young lady whose name was the same.

Next morning a long Lawyer’s letter I got,

I was told their client, Miss Stove, was red hot

Against Peter Carmichael her rage knew no bounds

And to cool this Stove down it would cost fifty pounds.

But I’ll gie ye correct, etc.

A congress was held, and I tried to explain,

But Beaconsfield and Bismarck would have found it in vain,

Wi’ a’ their experience, to prevail upon her,

And come back frae Shetland wi’ peace and wi’ honour.

I thocht on a plan to console this sweet dame

Since naething but riches could settle her claim;

I would gan out to Cyprus, though it cost me some siller,

And houk up some diamonds and sen’ them till her.

But I’ll gie ye correct, etc.

Some comedians I’ve kent in their efforts to please

Have got into trouble by such trifles as these

There’s some folk aye sees something rude in a sang

While their pure-minded neighbours can see naethang wrang.

But now to conclude-I am happy to say-

This storm in the north has complete passed away;

Like our Government lately, to end the contention,

I settled it up wi’’ a secret convention.

But I´ll gie ye correct, etc. (Houston 86-87).

Constructing a mental picture for his “friends”, he takes his audience along on a journey “far frae hame” to specific geographical regions, and evocatively to the “famed Shetland Isles.” Houston is playing to national sentiment by referencing the geography of Scotland in the lyrics about his experiences and creating an image of place that acknowledges the sensibilities of his Glasgow audience who for a variety of reasons, including migration might have memories of their own about northern landscapes. His audience shares in his experience. By situating the story in Scotland, Houston in the words of Alasdair Cameron, offered in particular to the Scots in the audience the “sheer pleasure of linguistic and cultural recognition” and for both the Scottish and members of the Irish community in the audience “the escapism afforded by comedy” (Findlay 34).

Comedy also allowed Houston to offer a deft and topical explanation for the incident that had shadowed him on the summer tour. At the same time as he was admitting to the complexities of the legal wrangling caused by his gaffe, he was also comparing his situation to the complicated and protracted diplomacy between the British Prime Minister Disraeli, now Lord Beaconsfield, and his German counter part Chancellor Bismarck. A compromise of sorts was finalized among the protagonists, not only between Stove and Houston, but also those attending the Berlin Congress, which ended with the Treaty of Berlin on the 15th of July 1878. Houston’s assumption that his comments would meet with the approval of the audience is an example of the interests of two audiences converging over an issue that was making headlines in the press. Houston works with his audience’s familiarity with political leaders and international events on the world stage, information that they gleaned from the latest telegraphic news in the press. A reference to Cyprus in this song assumes the audience knew about the cession of Cyprus by Turkey to Britain as an outcome of the Treaty of Paris, which had only just occurred. Significantly, Houston’s visit to Lerwick coincided with this event and it is obvious that he read about the diplomatic wrangles via the Telegraphic News Reports (per Orkney and Shetland Cable) in the pages of The Shetland Times while he was on tour. The newspaper assiduously covered the events, reflecting a keen local interest over the “Eastern Question” and the complicated negotiations over territory involving such prominent individuals as Disraeli, Bismarck and the Tsar of Russia. The consequence for Houston of these detailed accounts were immediate and relevant.Houston could use the high level diplomatic escapades between various world leaders at the Congress as a rhetorical foil when arriving back in Glasgow from his Northern Circuit by playfully describing to his audience the litigation of Miss Stove who finally settled on fifty pounds, after tense negotiations which “cooled this stove down”, thus allowing Houston to leave Lerwick “wi’ peace and wi’ honour.”

In the concluding paragraph of the Autobiography, Houston muses over writing his story “in a plan and homely way” in order to “bring back recollections of bye gone days” (128).He acknowledges precisely the frustrating issue, which historians of Scottish Victorian theatre face when attempting to reconstruct performances from this period. The nature of the performances in the 19th century, before technology enabled them to be tape recorded, or filmed survive only in the valuable musings of autobiographies, in professional publications such as the Era and its specialized column “Provincial Theatres, from our own correspondents” and in the reviews contained in local newspapers. According to the Scottish theatre historian Paul Maloney “with such a shortage of documentation, the main sources of information have been newspaper columns” (92). Consequently, the nature of the performance can often only be conjectured from these reviews. Houston’s Autobiography, however, when combined with The Shetland Times accounts supplements and extends our knowledge of one particular summer tour in the Northern Isles of Scotland. Still there will always be large gaps in our imaginative recreation of these performances. The unique and primary form of communication in the theatre is as Houston attests the voice, in all its ranges, cadences, rhythms and dialects. Thus it is particularly difficult for an actor to leave a legacy. Houston puts it succinctly:

I am quite well aware the stories and songs and the sketches will not strike my readers so vividly as if they heard me telling them myself. The modulation of the voice, the national accent, and the art of suiting the action to the word are wanting (128).

His invaluable Autobiography while it does not supply the answers to this dilemma, can, when supplemented by newspaper accounts, offer valuable insights into the transient quality of theatre and the nature of performances that summer in Lerwick.

Works Cited

Abrams, Lyn. Myth and Materiality in a Woman’s World: Shetland, 1800-2000. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005. Print.

Baynham, Walter. A Brief History of the Glasgow Stage. Glasgow: Robert Forrester, 1892. Print.

Burns, Robert. The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns. ed. Jerome Kinsley. Oxford: Oxford University Press,1968. Print.

Cameron, Alasdair and Adrienne Scullion, eds. Scottish Popular Theatre and Entertainment in Victorian Scotland. Glasgow: Glasgow University Library, 1996. Print.

Findlay, William. “Scots Language and Popular Entertainment in Victorian Scotland: the Case of James Houston.” Eds. Alasdair Cameron and Adrienne Scullion. Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1996.15-38. Print.

Houston, James. Autobiography of James Houston, Scottish Comedian. Glasgow and Edinburgh: Menzies and Love, 1889. Print.

Maloney, Paul. Scotland and the Music Hall. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. Print.

Manson, Thomas. Lerwick During the Last Half-Century: 1867-1917. (1923). Lerwick: Shetland News Office, 1991. Print.

Prior, Mary. Fond Hopes Destroyed: Breach of Promise Cases in Shetland, 1823-1900. Lerwick: The Shetland Times Limited, 2005. Print.

Robertson, Margaret Stuart. Sons and Daughters of Scotland (1800-1900). Lerwick: Shetland Publishing Company, 1991. Print.

“New Years Entertainments.” Aberdeen Journal (Aberdeen) 4 January 1879. Print.

“Provincial Theatres from our own correspondents.” The Era (London) 17 March 1878. Print.

“Provincial Theatres from our own correspondents.” The Era (London) 9 June 1888. Print.

“General Notices.” The Shetland Times (Lerwick) 22 June 1878. Print.

“Musical Entertainments.” The Shetland Times (Lerwick)13 July 1878. Print.

“Local and District News.” The Shetland Times (Lerwick) 20 July 1878. Print.

“Musical Entertainments.” The Shetland Times (Lerwick) 26 July 1884. Print.